Scientific research

Questions for Professor David Sander

Director of the Swiss Centre for Affective Sciences (SCAS - CISA in French)

Video Interview with Professor David Sander (in French)

Neurosciences

Photography: David Sander, © CISA - Sophie Jarlier

Q: There has been much talk about neuroscience in recent years. Could you define what neuroscience is in a few words?

DS: What is neuroscience? There are at least two ways of defining what it is. The first is to define neuroscience by the fact that the brain is a focus for study in its own right; in which case a neuroscientist can be defined as someone who studies the brain and wishes to understand the brain’s structure and the way in which it functions. That would be the first general way of defining neuroscience.

The second would be to define neuroscience by the fact that it corresponds to an approach, a discipline, a subject area or even a perspective: this could mean that we could be interested in psychology in general with a neuroscientific approach. We might be interested in how our brains make possible perception, attention, memory, learning forms, language, reasoning, decision-making and, of course, emotions.

The idea could therefore be to try and understand the complexity of psychological phenomena by taking an interest in the brain because we are obviously well aware that psychological processes happen within the brain’s complex architecture. However, in such a case, the focus of study itself would not typically be the brain, but could be memory, emotions, decision-making and, as is increasingly the case, school learning, from a neuroscientific point of view.

Q: In your opinion what are the most striking elements that account for the attention paid to neuroscience in recent years?

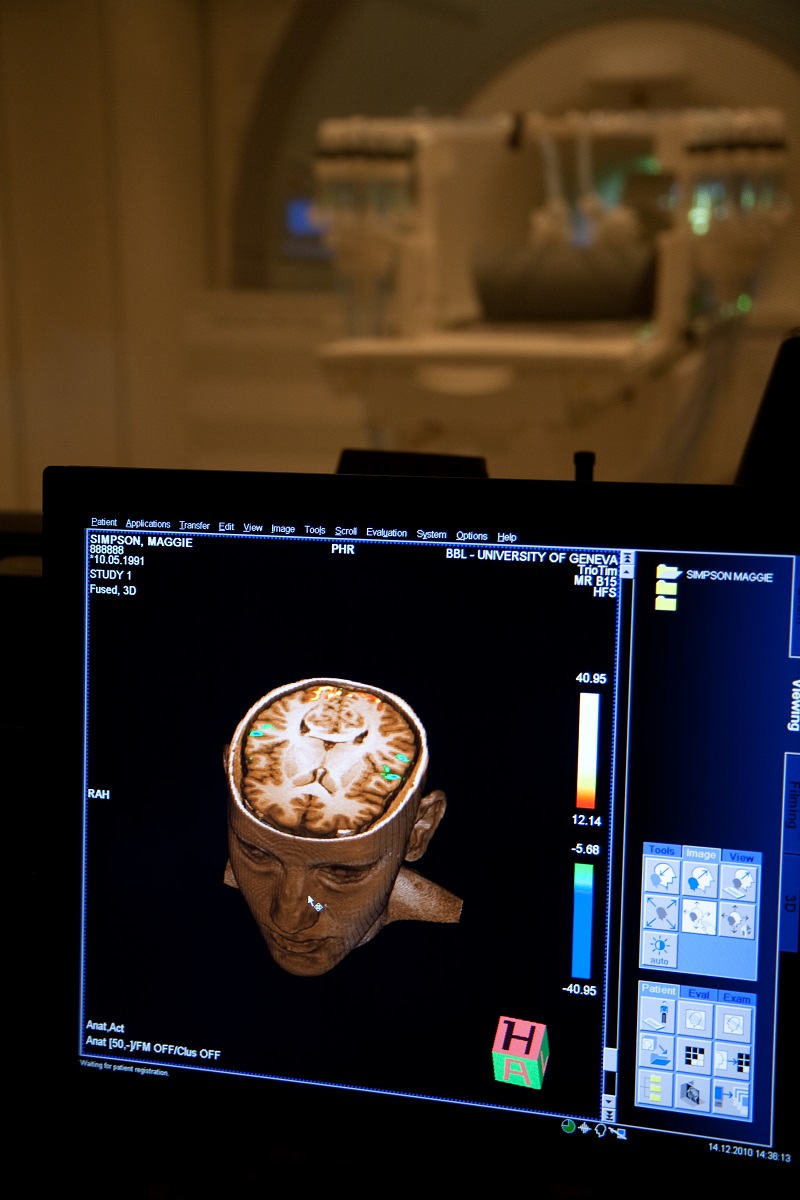

DS: Over possibly the last 10 to 15 years there have been enormous developments in neuroscientific research, particularly with regard to its impact on society and public interest in the study of the brain. This fascinates many people, and rightly so! There are certainly a number of reasons for such a keen interest. One reason, I think, has to do with methodology, that is to say over, perhaps, the last 20 years techniques have been developed that make it possible to measure brain activity non-invasively; for example, functional magnetic resonance imaging is a fascinating method that allows researchers to analyse the various regions of the brain involved in the various forms of perception, emotion, decision-making or this or that form of learning.

Researchers now have models of how the brain functions and the fact of observing the brain’s activity, in my opinion, goes some way towards explaining this passion that people have for the brain. Another reason stems from the fact that people with quite specific forms of brain damage have quite specific psychological and behavioural problems, leading to the fact that everybody now realises that there is a link between certain areas of the brain and certain psychological or behavioural problems; everybody is therefore now aware of this quite direct relationship between human complexity and the complexity of the brain.

Not only do these methodological aspects exist but so does the explanatory aspect, that is, there is the impression that once we will have really understood how the brain works, we will have understood many things about human nature, the human mind, about social interactions or even about learning situations.

Therefore all human situations clearly have a counterpart in terms of brain activity and we now have many tools to try and measure that. Hence the fascination that I think almost everyone has for the brain.

SCAS (CISA in French)

Q: You are director of the Swiss Centre for Affective Sciences. What exactly do they do there?

DS: The Swiss Centre for Affective Sciences - SCAS – is a University of Geneva centre hosting the National Centre for Affective Science Research. The term “affective science” refers to the fact that we are studying affective states, meaning all affective phenomena, mainly emotions but also other affective phenomena such as moods, preferences or even motivations with the help of all pertinent academic disciplines. For example, our centre brings together research in psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, literature, economics and informatics.

Our centre is very inclusive because we have fully understood that in order to really understand a phenomenon as complex as emotion a great number of approaches are of use. Among our goals are those of understanding how emotions are triggered, understanding what is happening in our bodies when we have emotions, understanding how these emotions can be controlled, understanding the effect of emotions on other cognitions, such as, for example, memory, attention, learning or decision-making. To do this we try to take advantage of all the methods that are currently available in neuroscience and in social science and the humanities.

Q: As teachers or educationalists, what are the areas or broad sectors in neuroscientific research that concern us directly or indirectly?

DS: Well, obviously, research in affective science, cognitive science and in neuroscience has a potentially major application across wide areas of society. In particular, the area pertaining to schooling is one that can and will be able to benefit from research carried out in these areas. This dynamic began several years ago.

In effect, the school is a place of learning for life, but also, of course, a place where knowledge is learned: the curriculum. It is therefore obvious that if we understand the mechanisms whereby the individual can learn and reason better, the mechanisms whereby an individual will express, feel and control this or that emotion, the mechanisms whereby an individual is able to give his sustained attention to a situation, such that he will encode a situation, consolidate and remember it, in short, if we manage to understand an emotion and its effects on a whole series of cognitive mechanisms, this would make it possible to work with the educational sciences and teachers to develop more suitable curricula taking account of children’s inter-individual differences to optimiser pupils’ learning possibilities. Thus, ‘traditional’ learning tasks, as proposed in the school curriculum, would be made easier, but also why not learn emotional competences, such as controlling one’s own emotions or understanding other people’s emotions.

School could be a place where we not only learn what is traditionally taught but also what is important elsewhere in society and for people’s lives. From this point of view, it seems to me that research done in the laboratory, even if there is a lot of groundwork to be done to try and see how it could be applied, has immense potential, we really have to work hand in hand with professionals, with experts in schools – educators who know their terrain – because while it is true that we have our limits in our laboratories, from what we see from research being carried out, we really think that there is potential for application. When we start to understand the psychological and brain mechanisms underlying learning, attention, memory, reasoning, language, social cognition and emotions, we realise that these can be useful to teachers.

Q: What are the bibliography and internet links about SCAS that are of interest to teachers and educators?

Regarding SCAS in general, the following link presents our research projects:

http://www.affective-sciences.org/content/research

This series of projects looking at emotional development, particularly in the school environment, could be of interest:

http://www.affective-sciences.org/content/emotional-development

Most of my publications are available at this link:

http://cms.unige.ch/fapse/EmotionLab/publications

http://cms.unige.ch/fapse/EmotionLab/books/books.html

Professor Edouard Gentaz, a member of SCAS, recently co-ordinated an edition of the journal ANAE aimed specifically at teachers and educators providing them with an initial introduction:

http://anae-revue.over-blog.com/2015/12/anae-n-139-apprentissages-cognition-et-emotion.html

Schools

Q: Are there research projects that really link laboratory work with the educational everyday (school, classroom)?

Neuroscience, and, more generally, the affective and cognitive sciences, have been playing a key role for approximately 10 years in bringing together experts in the educational sciences to create initiatives aimed at developing ‘evidence-based education’. There are a number of new research centres interested in the links between neuroscience, psychology and education aimed expressly at establishing the link between laboratory and classroom. This research is published not only in books but in scientific journals. This even led to the creation of a new scientific journal entitled “Mind, Brain, and Education” in 2015.

The contribution of neuroscience and affective and cognitive science comes on the one hand from new research projects and intervention programmes establishing links between laboratory and school, and, on the other hand, from the use of research results and conclusions to inform the field of education in partnership with experts in the educational sciences. Such research projects concern work on reading or mathematics (see the article by Stanislas Dehaene below) as much as work on the emotions (see the RULER programme below). Sometimes these studies trigger controversies and it would seem that to really achieve a link between the laboratory and the educational everyday a step that is as important as it is rare would be for scientists, educational experts and teachers (not to mention pupils and parents) to work hand in hand to avoid minimising the complexity of the field and its variables that are difficult to control in the laboratory.

Q: What practical relations could or should be established between neuroscientific researchers and educational practitioners?

It should be possible to develop joint research projects that go from the laboratory to the school. If there is a very precise question that could be applicable for the educational world, it is possible to carry out laboratory studies to test hypotheses in as controlled a manner as possible from the experimental methodology point of view, then, step by step, together with practitioners, to take these experiments into schools, and, using intervention mechanisms in the classroom, put in place protocols to test whether an effect observed in the laboratory is sufficiently generalizable, strong and robust for subsequent application in a school programme.

A concrete way of proceeding, therefore, would be to design an in-school laboratory research programme involving a number of schools. For example, as part of SCAS, we have a project to test links between pupils’ emotional competencies, types of educational approach and school learning situations. We could, for example, look at the effects of controlling emotions and of understanding one’s own emotions not only on the well-being of children but also on their school performance.

A few weblinks:

International Mind, Brain and Education Society (IMBES)

http://www.imbes.org

The journal « Mind, Brain and Education » http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1751-228X

Conferences on educational science and education (in French)

http://eduscol.education.fr/pid26704/sciences-cognitives-et-education.html

Series of lectures in French at the College de France “L’apport des sciences cognitives à l’école : quelle formation” (in French):

http://www.college-de-france.fr/site/stanislas-dehaene/symposium-2014-2015.htm<br>

http://moncerveaualecole.com

particularly:

http://moncerveaualecole.com/education-et-sciences-cognitives-le-coup-de-gueule<br>

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_New_Vision_for_Education.pdf

Mind, Brain, and Education

http://www.gse.harvard.edu/masters/mbe

Emotional intelligence - RULER

http://ei.yale.edu/evidence/

By way of entry into this subject area, a collection of recent articles in French published by the ANAE - Approche Neuropsychologique des Apprentissages chez l’Enfant - ANAE N° 139 - Apprentissages, cognition et émotion (special issue compiled by Professor Édouard Gentaz).

http://anae-revue.over-blog.com/2015/12/anae-n-139-apprentissages-cognition-et-emotion.html