Practice of philosophy

Tools to think

Learning to think by yourself and for yourself

In Geneva, the history of the practice of philosophy began with a teacher at the Ecole Active de Malagnou, Paule Watteau. She had managed to get hold of equipment from Matthew Lipman (then unknown in Geneva) and she led philosophy workshops with her 9-year-old students. At the time, she was the only one to do this.

Film “La pratique de la philosophie avec les enfants” (Ecole Active de Malagnou)

Then, following a lecture given by Michel Sasseville in 1998 in Lausanne, a group of people gathered to create an association whose mandate was to promote the practice of philosophical dialogue. The ProPhilo association was born and Paule Watteau was President for several years.

By Alexandre Herriger

The History of practicing philosophy with children and adolescents

The idea of practicing Philosophy with children or adolescents dates back to the ancient Greeks and Socrates will no doubt remain an iconic figure in the movement which was then just beginning. Socrates liked to engage young people in an inquiry about their conception of the world. He involved them in dialogues in which they discovered knowledge as yet unrevealed to them. This approach called maieutic aims to bring out hidden knowledge inside oneself and is characterised by a questioning or personal enquiry. This in itself challenges the thinker and causes reflection.

This use of philosophical dialogue has gradually disappeared, giving way to the world of authors, exchanges being written down and answers to the big questions of existence taking on the form of voluminous works.

At the end of the sixties an American philosopher, Matthew Lipman and his collaborator, Ann-Margaret Sharp had the original idea of introducing the practice of philosophical dialogue into the world of education, making it a teaching tool to help children develop their capacity to think. They decide to write stories for children incorporating the various sub-disciplines of philosophy. Gradually they developed a whole curriculum whereby through a reading in class, children discover logical rules, ethical, metaphysical and aesthetic values. Their intention at the start, slightly different from that of Socrates was to enable children from their early years to develop a “good head”, to learn the basic mechanisms of logical reasoning by continually questioning, challenging and evaluating ideas.

Objectives for the practice of philosophy according to Matthew Lipton

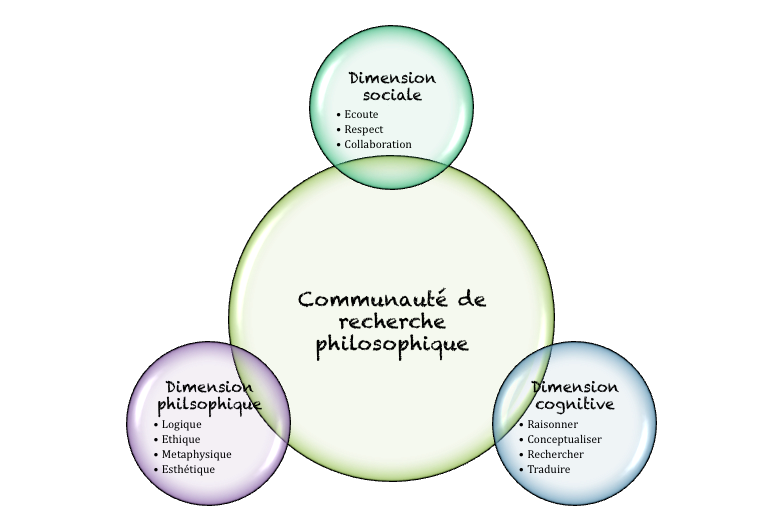

For Lipman and Sharp, the main goal of teaching philosophy at school is to awaken a critical, vigilant and creative thought process in children, strengthening their capability to make judgements. This implies work on certain thinking skills, ranging from reasoning through research to conceptualisation. Lipman and Sharp propose a framework called the philosophical research community or the community of inquiry. The term “research community” is a formula that Lipman borrowed from Charles Sanders Peirce, considered the founder of pragmatism Peirce sees pragmatism as a method for clarifying ideas relying on scientific methods to solve philosophical problems.

A community of inquiry is therefore a group of people (some talk of a committee) working together who collaboratively engage in purposeful critical discourse and reflection to construct personal meaning and confirm mutual understanding. Engaged in a philosophical debate they apply methods of research such as questioning, hypothesis, examples and counter examples, observation and self correction. It is made up of several dimensions:

COMMUNITY OF INQUIRY

Social Dimension

Cognitive dimension

Philosophical dimension

-

Listening

-

Reasoning

-

Logic

-

Respect

-

Conceptualizing

-

Ethics

-

Collaboration

-

Inquiring

-

Metaphysics

-

Translating

-

Esthetics

These different dimensions offer a curriculum framework in which young people are stimulated intellectually and through which they can learn to weave relationships based on respect and listening to others.

The main lever of this model is the use of dialogue implying that language and interaction between students play an integral part in this reflective phase. However, depending on the context and environment the objectives and the means may vary. For example in Quebec, teaching philosophy to children is used to prevent violence. It is also often used in the educational context of citizenship. There are multiple applications and the initial goals are giving way to more and more new objectives.

There are also so many ways of doing philosophy with children or teenagers. Lipman has inspired as many teachers as he has philosophers who in turn have imagined other ways for young people to study philosophy. These approaches offer other objectives and other means which will obviously affect the role of the adult /teacher

Different approaches to practising philosophy with children and adolescents

All the different approaches in philosophy crystallize around different people. Some have interpreted the work of Lipman and propose variants of the research community, while others have wanted to reinvent the approach and thus offer other models.

In addition to the Lipman approach, there are three major trends in philosophy for children.

-The approach of Michel Tozzi, trainer at the IUFM of Montpellier bases this practice on debate, conceptualization and problematization through democratic and philosophical discussion (DVDP). Discussions are organized around jobs attributed to certain students.

-The approach of Oscar Brenifier, French philosopher and author of several books for children, focuses on reflection around an opinion with a view to going further. It also stimulates students to think about the contrasts between good and evil, justice and injustice, being large and being small. His approach is Socratic and the animator is very present in these workshops.

http://www.pratiques-philosophiques.fr/

- The approach of Jacques Lévine, French psychoanalyst puts forward a structure whereby children are encouraged to talk in order to discover the subject in hand. In so doing, a new relationship to oneself and others can develop. The silent presence of the adult enables him to observe the students and so better understand their potential.

http://agsas.fr/les-ateliers-de-reflexion-sur-la-condition-humaine

Summary of the different approaches

The importance of philosophical dialogue

Dialogue is one of the many ways we can talk to ourselves. Chatting, discussions, conversations, monologues, debates are all different ways to exercise words. However dialogue opens up a particular space. Based on the sharing of ideas it encourages a face-to-face which often moves towards something else - discovering other ideas - inventing together. As long as each one takes into account what has been said , dialogue advances constantly. Research, understanding, clarification, and verification are all steps in a journey, the outcome of which is unpredictable. Above all it offers an environment where everyone is equally capable of truth and meaning (Conche, 1993, p. 38-39) which helps break the logic “if I’m right, you are necessarily wrong!”

A philosophy workshop in class favours dialogue rather than debate as it is not a question of rhetoric but a quest towards collective research, the result of which depends on the participants. Looking for answers, but also looking for criteria to support a definition or to make a distinction with examples and counter examples. Philosophical dialogue is a mutual inquiry based on the principle that the more points of view there are, the better we understand what there is to understand. There are no winners and no losers - it is open, based on collaboration.

The practice of philosophical dialogue promotes important skills ranging from communication to collaboration through the process of critical and creative thinking.. All of these skills appear on the new study plan of the Suisse Romande, and working with students on philosophy is an excellent way to reinforce these skills. Moreover it offers students an open space in which they can develop their ideas with the support of an adult who can help them go beyond conventional wisdom.

The roles of the animator in teaching philosophy to children and teenagers

Depending on the approach chosen, the role of the animator will vary greatly. According to Jacques Lévine the teacher remains voluntarily silent, whilst in other approaches the animator will intervene during exchanges. What should the role be? This is the subject of a number of reflections - namely the position or posture of the adult which plays a key role in the achievement of the objectives. In other words, when do we intervene and for what purpose?

In no case should a class be taught ex-cathedra in which the students are led to memorise what philosophers have said. Neither is it a question of the students “borrowing” the reflections the philosopher made to come to his conclusions. In fact we should say that philo in primary and secondary schools is not to be taught but practised as in music.. The instrument we are learning to play however is thinking and the teacher must encourage the students to do this by themselves.

The animator has an arsenal of questions stimulating different thinking skills, helping the students to go further than the sharing of opinions to the real analysis of ideas. His role is not to give ideas but to support students in their thinking, leading them towards ideas he thinks appropriate for their research. The teacher becomes a moderator, questioning the students and encouraging them to go further than an expressed opinion, to bring up counter arguments, helping them to reason and conceptualise.

In this context, the teacher/animator needs to carefully consider the processes i.e. the way students organise their own thoughts and research.. He should also enable them to see a multitude of opinions and to ensure that they integrate logical, moral, aesthetic and metaphysical considerations in their reflection. His role is also to deconstruct certain prejudices which could rise from discussions. In fact the job description of a philosophy teacher differs greatly from the traditional one. M. Gagnon points out that “the teacher must take on the opposite of a traditional role since the changes occurring in a philosophical research community (as opposed to a normal classroom situation) presuppose a waiving of the magistral form of teaching to make way for questioning and dialoguing so that students can practice their reflective and critical thinking skills” (Gagnon, 2005, p.1).

The practice of philosophy in Geneva

In Geneva, the history of the practice of philosophy began with a teacher at the Ecole Active de Malagnou, Paule Watteau. She had managed to get hold of equipment from Matthew Lipman (then unknown in Geneva) and she led philosophy workshops with her 9-year-old students. At the time, she was the only one to do this.

Film “La pratique de la philosophie avec les enfants” (Ecole Active de Malagnou)

Then, following a lecture given by Michel Sasseville in 1998 in Lausanne, a group of people gathered to create an association whose mandate was to promote the practice of philosophical dialogue. The ProPhilo association was born and Paule Watteau was President for several years. The work of these volunteers consisted of some training with Michel Sasseville plus the distribution of educational materials. The ProPhilo association now offers various services: training, coaching, philosophical dialogue practice, philosophical foundations courses, exchange of practice, etc. (www.prophilo.ch)

A partnership between proPhilo and the IFP in the early 2000s made the practice of philosophical dialogue more accessible to teachers of private schools in Geneva. Very soon many of them wished to incorporate this practice into their teaching. So far, a dozen private schools in Geneva have regularly practiced philosophy with their students for several years. Some of them offer philosophical workshops to students across the curriculum.

In 2005, Paule Watteau was contacted by the DIP to offer a course on philosophy in the classroom to the Department of Further Education. Some teachers in the state primary schools were introduced for the first time to the idea of teaching philosophy to children. Following the death of Ms. Watteau in 2007, the course was taken over by Alexandre Herriger in 2008. It is still in the training catalogue and every year several institutions apply for training in philosophical dialogue. Today, Mr Herriger has responded to more than 20 requests for training in State primary schools and he is currently working with 3 State secondary schools in which the practice of philosophy is integrated into the curriculum.

What is Eduphilo?

Eduphilo is a professional interface which in partnership with institutions, provides training and support in philosophical dialogue at school or elsewhere. By coaching heads of schools as well as the teaching staff Eduphilo provides educational support for anyone who wants to introduce this practice in their classes in school, or even within a company.

Eduphilo is also a platform for development - particularly educational material. Different projects involving the practice of philosophical dialogue to specific hardware is sometimes required both in terms of content as well as in form. Through the production of philosophical stories for young people or more educational material for teachers, this platform is the ideal location for projects to develop and succeed.

Further readings (in French):

Bibliography

1. Reference books (in French)

-

Brenifier, O., La pratique de la philosophie à l’école, Éd. SEDRAP Éducation, Toulouse, 2007.

-

Caron, A., (sous la direction de), Philosophie et pensée chez l’enfant, Éd. Agence d’ARC inc., Ottawa, 1990.

-

Daniel, M. F., Pour l’apprentissage d’une pensée critique au primaire, Éd. Les Presses de l’Université du Québec, Montréal, 2005.

-

Gagnon, M., Guide pratique pour l’animation d’une communauté de recherche philosophique, Éd. Les Presses de l’Université Laval, Québec, 2005.

-

Lévine J. et Moll J., Je est un Autre. Pour un dialogue pédagogie-psychanalyse, Éd. ESF, Paris, 2001.

-

Leleux, C., (sous la direction de), La philosophie pour enfants. Le modèle de Matthew Lipman en discussion, Éd De Boek, Bruxelles, 2005.

-

Lipman, M., À l’école de la pensée. Enseigner une pensée holistique, 2ème édition, trad. de Decostre N., Éd. De Boek Université, Bruxelles, 2006.

-

Lipman, M., La découverte de Harry Stottlemeier, Éd. J.Vrin, Paris, 1978.

-

Lipman, M., La recherche philosophique, guide d’accompagnement du roman La découverte de Harry, trad. de Marie-Marthe Ménard, AQPE, Québec, 1996.

-

Lipman, M., Philosophy goes to school, Éd. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1988.

-

Sasseville, M., (sous la direction de), La pratique de la philosophie avec les enfants, Éd. Les presses de l’université Laval, Québec, 1999.

-

Sasseville, M., et Gagnon M., Penser ensemble à l’école : outils d’observation pour une communauté de recherche philosophique, Éd. Les presses de l’université Laval, Québec, 2007.

-

Tozzi, M., Penser par soi-même : initiation à la philosophie, 5ème édition, Éd. Chronique sociale, France, 2004.

2. Suggested readings (in French)

-

Dewey, J., How we think, Éd. Prometheus Books, N. Y., 1991.

-

Lafortune, L., Mongeau, P. et Pallascio, R., Métacognition et compétences réflexives. Éd. Logiques, Montréal, 1998.

-

Morin, E., Introduction à la pensée complexe, Éd. ESF, Paris, 1990.

-

Reboul, O., La formation du jugement, Éd. Logiques, Montréal, 1992.

-

Santuret, J., Le dialogue, Éd. Hatier Paris, 1993.

-

Splitter, L. et Sharp, A. M., Teaching for better thinking, Éd. Acer, Australie, 1995.

-

Tozzi, M., Débattre à partir des mythes : A l’école et ailleurs, Éd. Chronique sociale, France, 2000.

DVD (in French)

-

Des enfants philosophent, série documentaire, Michel Sasseville, Université Laval, Québec, 2005.

-

Stimuler la pensée et le dialogue critiques chez les enfants, Marie-France Daniel, Université de Montréal, 2007.

-

Ce n’est qu’un début, documentaire, Le pacte, France, 2010

3. Bibliography dedicated to children (in French)

3.1 Collection from Matthew Lipman books (available in French trough proPhilo)

-

Ellfie et son manuel pédagogique Relier nos idées ensemble (1p-2p)

-

Kio et Augustine et son manuel pédagogique S’étonner devant le monde (3p-4p)

-

Pixie et son manuel pédagogique A la recherche de sens, (5p-6p )

-

La découverte de Harry et son manuel pédagogique La recherche philosophique (7p-8p)

-

Lisa et son manuel pédagogique La recherche éthique (début du secondaire)

-

Suki et son manuel pédagogique La recherche esthétique (secondaire, en anglais seulement).

-

Mark et son manuel pédagogique La recherche sociale et politique (fin du secondaire).

3.2 Collection from Oscar Brenifer books (available in French in libraries)

-

Collection PhiloZenfants, édition Nathan, Paris 2008

-

Comment sais-tu que tes parents t’aiment ?

-

Peux-tu faire tout ce que tu veux ?

-

L’argent rend-il heureux ?

-

Sommes-nous tous égaux ?

-

Pourquoi je vais à l’école ?

-

Les sentiments c’est quoi ?

-

Vivre ensemble, c’est quoi ?

-

Le livre des grands contraires philosophiques, édition Nathan, Paris 2009.

-

Le livre des grands contraires psychologiques

-

Le sens de la vie

-

C’est bien, c’est mal

3.3 Collection “les goûters philo”, Michel Puech and Birgitte Labbé (available in libraries)

-

L ‘amour et l’amitié

-

La beauté et la laideur

-

Le bien et le mal

-

Le bonheur et le malheur

-

Ce qu’on sait et ce qu’on ne sait pas

…

3.4 Collection from books dedicated to the prevention of violence (available in French trough proPhilo)

-

Les contes d’Audrey-Anne, de Marie-France Daniel, et son manuel pédagogique Dialoguer sur le corps et la violence, Edition Loup de

-

Gouttière, Montréal, 2006 (disponible également en librairie ou sur amazone).

-

Nakeesha et Jessa et son manuel pédagogique Chair de notre monde (1p-2p), Ann Margaret Sharp.

-

Fabienne et Loïc et son manuel pédagogique Faire face aux tempêtes de la vie (3p), Pierre Laurendeau.

-

Grégoire et Béatrice et son manuel pédagogique Apprivoiser la différence, (4p), Pierre Laurendeau.

-

Misha et son manuel pédagogique Le fil de Misha (5p), Nathalie Côté, avec la collaboration de Michel Sasseville et de Mathieu Gagnon.

-

Romane et son manuel pédagogique Le fil de Romane (6p), Nathalie Côté, avec la collaboration de Michel Sasseville et de Mathieu Gagnon.

-

Hannah et son manuel pédagogique Rompre le cercle vicieux (7p-8p), Ann Margaret Sharp.

3.5. Other relevant books (in French)

-

Tête-à-tête, de Geert de Kockere, Edition Milan Jeunesse, Belgique, 2003.

-

Jamais content, Geert de Kockere, Edition Milan Jeunesse, Belgique, 2003.

-

Les philo fables, Michel Piquemal, Philippe Laguatrière, Edition, Albin Michel, France, 2008

-

Yacouba, Thierry Dedieu, Edition Seuil, France, 1994.

Weblinks (French speaking websites)

-

IAPC (Institue for the Advancement of Philosophy with Children)

-

ICPIC (The International Council of Philosophical Inquiry with Children)

-

SOPHIA (European foundation for the Advancement of doing philosophy with children

-

Diotime L’Agora : Revue internationale de didactique de la philosophie

-

Michel Sasseville Professeur de philosophie, Université Laval, Québec