Student grouping methods

By Béatrice Haenggeli

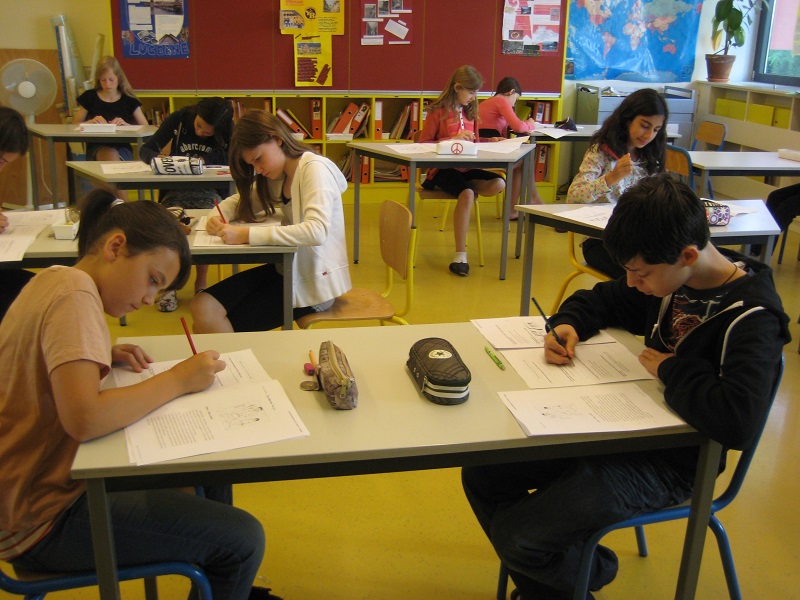

Photograph: © Ecole la Découverte

Learning at school can take many forms, depending on the methods used to work with students. The teacher chooses the appropriate work methods depending on the assigned goals and tasks that must be addressed and the conditions in which the learning process unfolds (student age, teaching staff, presence of another adult, etc.). The role of the teacher, the priority-ranking of knowledge-acquisition and the impact that the educational process has on the students – all of this can change depending on work methods.

Of course, these changes depend on the method of working with students chosen by the teacher. When using the frontal teaching method, for example, interaction between the teacher and the students takes place according to the “to-and-fro” principle. During group instruction there is interaction among the students, while the teacher remains on the periphery of the informational exchange. The conditions in which the learning process unfolds, such as student age, also influences the choice of teaching method. If we’re talking about little boys (3-6 years old), we observe a partial substitution of work method, insofar as the students are not yet able to concentrate on any one thing for an extended period of time.

Five different methods have been identified for working with students. The teacher can use various teaching methods over the course of the day, class or even a single lesson. Of course, certain situations are best suited to the frontal teaching method (if we’re talking about a whole class). First and foremost, this work method is typical of secondary and post-secondary educational institutions. Provided below is a description of the most frequently-used methods of working at elementary school, but other work methods can be used and entirely new ones can be developed.

“Frontal” method – full class

This teaching method is based on simultaneous work with all students in the class at the same time. In other words, it represents interaction between the teacher and the entire classroom. The method is sometimes referred to as “frontal teaching,” since the teacher stands at the front of the class and imparts his knowledge to the students, while at the same time supervising their activities during the lesson. The teacher and the students interact by conducting a dialog according to the “to-and-fro” principle. The teacher can also initiate a discussion among the students, but he always maintains a central position and leads the debates.

This work method makes it possible to communicate with all of the students at the same time and follow the general rules while relaying knowledge to everyone present. But it requires that the teacher be particularly attentive and capable of holding the attention of all students present so that all of them have the chance to absorb the new material. The teacher must be able to control the class leaders without allowing attention to wander. Extensive research on this issue indicates that this particular teaching method creates unequal conditions for the students, since it leads to the illusion that everyone learns the same way when in actuality – every student absorbs new information in his own way and at his own pace.

The collective teaching method is used more frequently than the others in the traditional school setting. In the first school grades, where the children are still adapting to the overall educational program and class size is high, this form of teaching is viewed as preferable. The method is also widely used in the older grades, although complemented by other methods. For instance, classes are divided into two groups – a kind of interim step between frontal, formal teaching and study in groups. It’s a strategy that allows the teacher to reduce student number while still working in the collective group.

Teaching method – working with groups

Under this teaching method, students are divided into groups in which they must work cooperatively to complete assignments. Groups can be made up of 2, 3 or 4 students, depending on the teacher’s objective and type of exercise. This teaching method presupposes the adult assuming a different position in relation to the students – he’s no longer “in front of the students” but standing to the side, ready to help if the need arises. He’s no longer in the role of teacher or judge but more of an organizer or colleague.

This kind of work necessitates that the teacher prepare in advance: how he plans to form the groups (homogenous or heterogenous, whether or not he’ll act as mentor, number of students per group, etc.), depending on the task at hand. It’s of no importance what type of work is being done: regular lessons, mastering new skills or building communication abilities. Attention must also be paid to how the students are expected to interact within the group: will their roles be identical or will each student have their own assigned task (for example, secretary, assistant, timekeeper, record-keeper, etc.)? Will they be able to choose their own group members or will the teacher take charge of that question?

One hundred years ago, Roger Cousinet, elementary school teacher and the first elementary school inspector, introduced the free group-work method, whereby children were able to choose their preferred type of activity from among those suggested by the teacher and organize themselves into groups in order to solve the assigned task. All types of activity were divided as follows:

- creative activity (manual work: handicrafts, gardening, animal husbandry) or “intellectual creativity” (drawing, painting, music, composition, poetry); arithmetic was added as a means of quantifying activity).

- educational activity: study involving animals, plants and/or minerals, physical or chemical phenomena, history and geography.

Groups are divided into types:

- HOMOGENOUS GROUPS: the groups are made up of students who have similar levels of knowledge in a particular field, although their age and expertise in other areas may differ. Such groups are formed in order to complete a specific task through the performance of a certain set of actions. They are created for a short interval of time, serving as a kind of “helper” in special situations. As soon as the students overcome any obstacles in their way, the group is disbanded or the teacher can create other groups.

- HETEROGENOUS GROUPS: such groups are usually formed by the students themselves, with their level of preparation of no real importance. They are shaped on the basis of friendliness among the students, which encourages the effective exchange of opinion, collective thought and the development of “socio-cognitive conflict.” It’s a highly-effective teaching method – particularly in cases when the assignment involves problem-solving, such as during math studies or analysis of the natural sciences, etc.

Mentor / apprentice method

The idea behind this teaching method is to put two students in a certain set of conditions. One of them is more prepared (the expert) than the other (the beginner). This method of teaching “in pairs” stimulates both the “expert” and the “beginner.” It is used to structure the learning process, while laying the groundwork for the equitable distribution of knowledge. Thanks to this teaching method, each student is engaged in the process, with everyone recognizing their own capabilities and achieving success. This teaching method can be used in the classroom, but also – and simultaneously – in multiple classes, bringing students from the same or different age groups together, and pursuing different educational goals.

Individual teaching method

This teaching method has two forms: “undifferentiated” and “differentiated.”

In the first instance, the individual assignments to be done by the students are similar. All of the students are under equal conditions and acting according to the same rules. This type of teaching makes it possible to compare the work of the students, and this role is performed by the teacher. It’s a work method that allows for the introduction of new concepts and evaluation of newly-acquired knowledge, but is also accompanied by certain challenges: how can we make sure that ALL of the students have mastered the new material? Moreover, it’s a method that demands a strict and effective system of control.

In the second, the assignments to be done by the students are different – they are formulated with a view to each student’s individual qualities, although the overarching teaching objective is the same for all of them. It’s a method that ensures a differentiated approach to, and autonomous work on the part of, each student. Assignments presuppose individual work and may differ: exercises (training), practical knowledge, research work, composition, computer work (lessons, games, creative writing), searching for material, etc.

Weblinks :

Summary tables on grouping methods (in French):

- Kindergarten: http://www.ia22.ac-rennes.fr/jahia/webdav/site/ia22/shared/maternelle/documents%20animations/AUTOUR%20DES%20MODES%20DE%20REGROUPEMENT.pdf

- Nancy Academy (2013 study): http://www4.ac-nancy-metz.fr/ia54-gtd/maternelle/sites/maternelle/IMG/pdf/GT_MAT_TABLEAUModes_de_regroupementSTAGE_DEC2013.pdf

Bibliography:

ALTET, M. (1994). Note de synthèse. Comment interagissent enseignants et élèves en classe ? Revue française de pédagogie, 107(1), 123-139.

ALTET, M. (1998). Les pédagogies d’apprentissage. Paris : PUF.

Astolfi, J. P., Peterfalvi, B., & Vérin, A. (2011). Comment les enfants apprennent les sciences. Paris : Retz.

Baudrit, A. (2005). L’apprentissage coopératif: origines et évolutions d’une méthode pédagogique. Bruxelles : De Boeck Supérieur.

MEIRIEU, P. (1991). Itinéraire des pédagogies de groupe. Apprendre en groupe ? Lyon : Chronique sociale.

MEIRIEU, P. Pourquoi le travail en groupes ? http://www.meirieu.com/ARTICLES/pourqoiletdgde.pdf

Paquay, L., Altet, M., Charlier, E., & Perrenoud, P. (2001). Former des enseignants professionnels: quelles stratégies? quelles compétences?. Bruxelles : De Boeck Supérieur.

Peeters, L. (2009). Méthodes pour enseigner et apprendre en groupe. Bruxelles : De Boeck Supérieur.

Toubert-Duffort, D. (2009). Penser et apprendre en groupe. De la fonction contenante au travail d’élaboration. Le Français aujourd’hui, (3), 45-54.