A Strategy for Boosting Student Engagement in Math

A four-step approach to group work can get students talking and boost their mathematical and metacognitive thinking.

I love watching do-it-yourself home renovation shows—there’s something magical about the before-and-after shots and seeing a transformation unfold. I always think that being a home renovator, working with a client to help their dreams become a reality, would be such a cool experience.

After a recent coaching experience with a high school math teacher, I realized that my role as an instructional coach is similar: I get to help teachers envision a transformation for their classroom and watch it come to life.

Identifying the Goal

The teacher asked me to give her feedback about how she could increase student engagement during whiteboard practice, a type of instruction in which she poses a review question on the board, asks students to solve it on their individual whiteboards as she walks around monitoring, and then checks the solution with the whole group.

Using a “strengths-based feedback” approach, the teacher and I carefully crafted a plan that changed the look, sound, and feel of her classroom: Silence turned into discussion and debate, and the students’ dependence on the teacher transformed into independence. Ultimately, we created a new strategy that replaced traditional whiteboard practice—which engaged most students—to a framework that engaged them all.

As I observed her teaching that first day, I noticed that her students were driven more by compliance than enthusiasm. They were seated in groups, but most of them weren’t talking to each other. In fact, I wondered if the room would sound exactly the same if they were seated in rows. I also noticed that there seemed to be three types of learners in the class: students who got the solution quickly and sat back waiting for the next question, students who needed some support but generally sought out the teacher for next steps, and students who struggled, often unable to finish the problem before the whole class went over it.

When the lesson was complete, I decided that my first question for the teacher would be: What would successful engagement look like and sound like to you? By asking the question in this way rather than giving her my thoughts, I encouraged the teacher to start brainstorming ideas with confidence.

As we debriefed, the teacher explained that she wanted to hear the students talking more, she wanted to be doing less direct instruction, and she wanted the students to work together to develop and communicate their understanding. I told her that I had observed that she had clearly created a positive classroom environment where work ethic and productivity seemed to be valued, which was a necessary first step, but that there was room for growth in terms of achieving the kind of active engagement she hoped for.

A New Approach: Try It, Talk It, Color It, Check It

We based the first two steps of the new approach we developed on the teacher’s desire for students to have time for both independent work and group collaboration before checking the final answer. During the first step, called Try It, students independently worked on the problem for two minutes; after that, they explained and compared their solutions in the Talk It step.

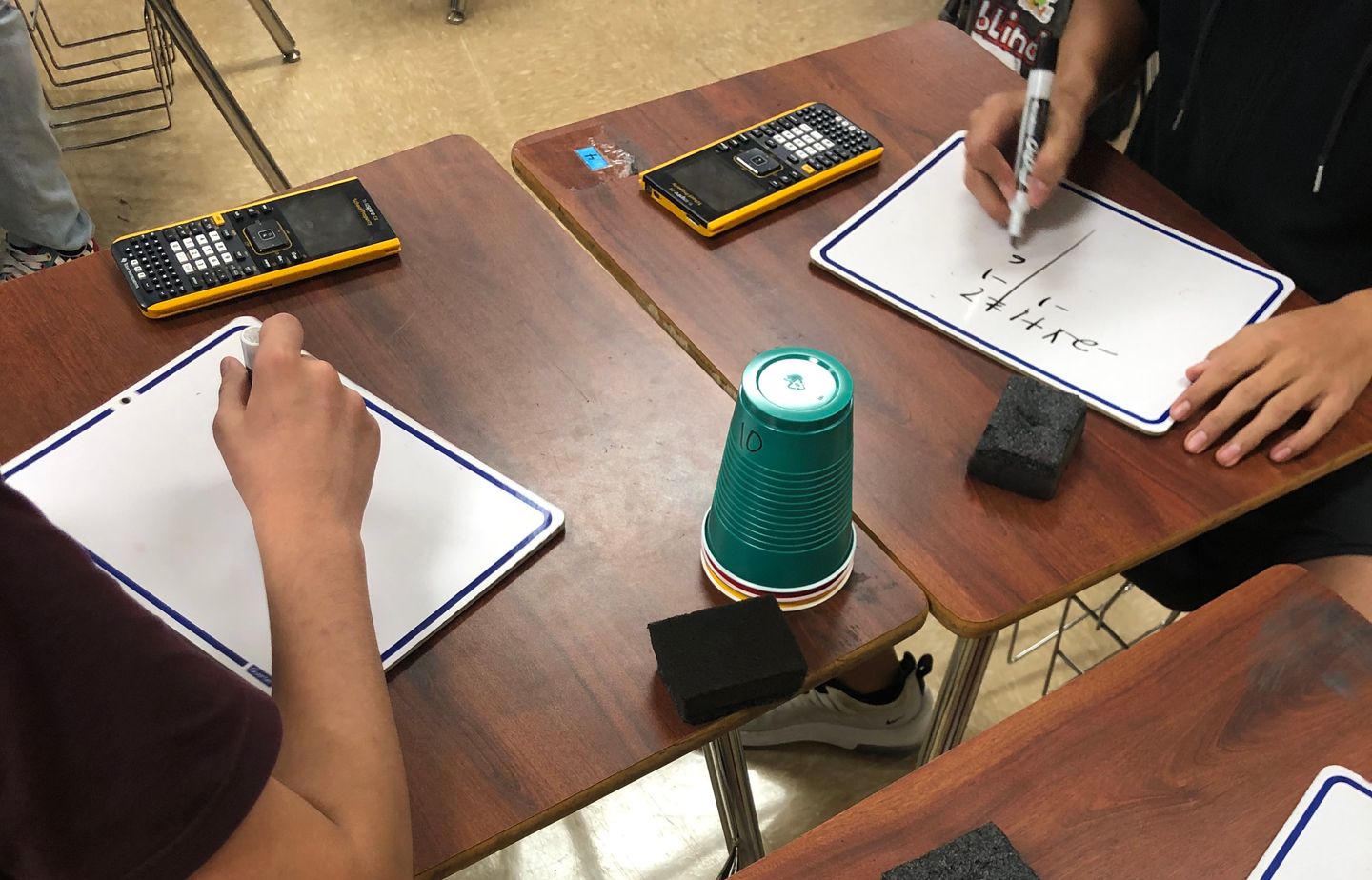

I had noticed colored cups at almost every table, and asked her what they were for. They were left over from a previous lesson, but we used them in the third step, Color It. In this step, questioning and conversation led to a process in which groups of students had to agree on one answer and use the cups to color code how confident they were about their solution, displaying a red cup if they thought they were probably wrong, yellow if they felt unsure, and green if they thought they had the correct solution.

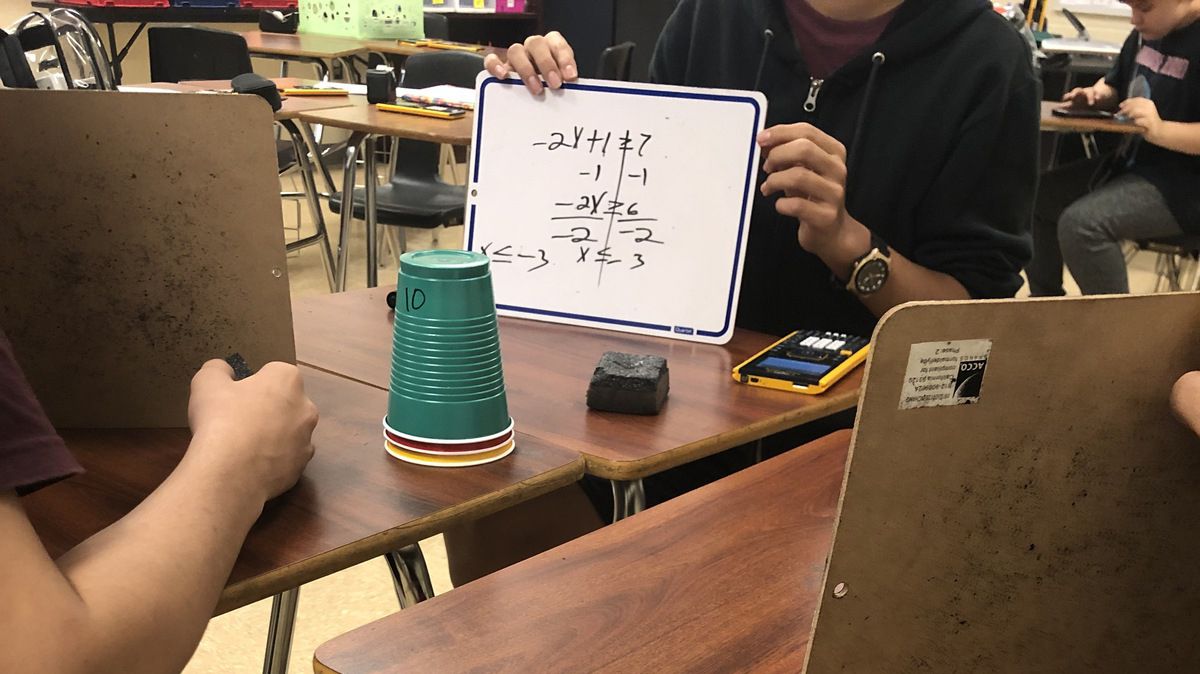

The teacher and I were excited that this self-evaluation step would enable her to gauge student understanding—as well as generate a greater sense of purpose and excitement. This led to our last step, Check It, in which each group held up their chosen whiteboard and engaged in a whole-class discussion on strategies and solutions.

Students review each other’s work in math class

When I observed the teacher’s next class using the new strategy, I was thrilled. Students were not only talking but excitedly debating. They were asking why and how as they explained their answers to each other. They were collaborating to select an answer and were on the edge of their seats after choosing a color, ready to hear the answer revealed. When the cups were mostly yellow, the teacher was able to meet students where they were for the Check It stage, rather than explaining the entire problem again and having students’ engagement drop. And students who had put out the green cup and were correct became the experts, confidently explaining their solution to the entire class.

From Idea to Practice

Mini coaching cycles like these have profound impacts on both student learning and teacher effectiveness. In this case, not only did we create a dynamic strategy that can be shared with other teachers, but the teacher achieved her goal of increasing engagement and collaboration. In the course of our conversation, this teacher identified knowledge and ideas she already had to develop a particularly effective instructional framework.

When I walked into the teacher’s room several weeks later and saw a poster hanging up that outlined the Try It, Talk It, Color It, Check It framework, I realized it had become the standard way she did whiteboard practice in her classroom. Just as I had envisioned revealing a house renovation to a client, watching this transformation unfold was a powerful and memorable experience.

Source: https://www.edutopia.org